Democracy - The Exercise of Personal Voice

Metcalfe Gallery, Brisbane Institute of Art, Windsor, Brisbane.

26 October - 6 November, 2018

An Essay to accompany the exhibition.

Democracy

by Carmel Lumley

With the election of President Trump in the USA, Democracy and how well it functions have become contentious topics.

Does it work?

Does it matter what the individual thinks?

Does an individual have any power to shape their own life let alone the country in which they live?

Below, I review the social and cultural background for our current understanding of Democracy and for Art in this context. I then look at how I've interpreted it for this exhibition.

Part 1 - Democracy

While its roots are in Ancient Greece, the Democracy we are most familiar with is its modern form. Articulated by Abraham Lincoln (in the Gettysburg Address of 1863) as a “Government of the People, by the People, for the People”, we understand it to be a construct where each individual is of equal value, each unique, and each with the right to self-expression. (1)

In a democratic state, citizens have an entitlement to vote, an obligation to contribute to, and a right to benefit from their government. This is expressed through a Rule of Law which aims to provide for majority rule, whilst safeguarding minority rights. The difficulty of this imperative is described by James Bovard, in his book Lost Rights: “Democracy must be something more than two wolves and a sheep voting on what to have for dinner." (2)

Universal Suffrage, each adult having a vote, is a 20th Century phenomenon in most countries (with Australia only fully recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voters in 1962). It was specified as a Human Right by the newly birthed United Nations as part of its Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, which gave form to the aspiration for each human being to have access to certain basic freedoms, powers, and protections within the structure of any society.

These core ideas, based around Equality, grew out of the fertile sociocultural soil of the previous 2 centuries. There was the Abolition of Slavery, the waves of Feminism, and the growth of Trade Union movements asserting the rights of workers. Communism and Socialism grew up as political/economic experiments, a reaction to the powerless position of the common person in Monarchies, Oligarchies, and Fascist states. And alternatively, in the expanding Capitalist system, the tension between allowing the Market free rein while still protecting individual rights played out. Many Asian, African, and Central/South American nations saw a changeover from Colonial rule to Autonomy, and they worked to greater or lesser extents to avoid the autocratic styles of their pasts. The struggles of these citizens were often made more difficult by the interference of other nation states and of big business in the form of multinational companies. In many countries, the inequalities and injustices faced by their First Nations people became mainstream issues, and the path to rectification incorporated into their nation’s story e.g. the Mabo Decision and the Treaty of Waitangi.

And so it became a global aspiration, that the power in any one nation state would no longer be wielded by any one person or cabal of individuals who were “ordained by God”, born into the right family, or possessed of military or financial might.

On the Work front, the Industrial Revolution reached full speed, and mass production mechanised and dehumanised the manufacturing process reducing the cost of everyday goods. It meant that simple conveniences were no longer the province of the wealthy. The development of Plastics reinforced this trend and, within a generation, more and more, that which had been reused and carefully maintained was exchanged for the cheaper disposable substitute. Even at the dinner table there was a change as an increasingly urban population was separated further and further from the source of the food that they ate.

Concomitant with these changes, the speed of transporting of people, goods and information increased. High speed communications meant that the community no longer relied on the newspaper or the radio to understand their world, and this was seen powerfully during the Vietnam War where television delivered its graphic horror directly to the home and thereby spawned a protest movement. War and its brutality could be seen at the level of the individual, rather than simply as a lamentable fight between nations for national interests. Citizens could make up their own minds based not only on what they were told, but also on what they saw. And all that was foreign, ghastly, beautiful, or banal could now turn up “live” in the lounge room or at the breakfast table. This ease of access could then be exploited by an increasingly sophisticated Advertising Industry.

How this played out in the prosaic as well as the esoteric is illustrated by this quote from Andy Warhol:

“What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you can know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke too.” (3)

All the while Science unravelled mysteries at every turn: subatomic, atomic, cellular, through to space, with the Moon landing and the Big Bang Theory. Education was also evolving. It came to be seen as a basic human right, a way of alleviating poverty, and poor access to it was challenged globally. This increasingly meant that threats such as World Hunger, Global Warming and Terrorism, and the difficulty in finding easy solutions to these problems, could be perceived and understood by everyone, albeit to varying degrees. We were becoming global citizens, a species amongst many.

What we understood it meant to be Human also expanded. Psychology, Neuroscience and Medicine, the Arts and the Social Sciences illuminated more and more of our internal and external landscapes, emphasising both our individual uniqueness and our overwhelming commonality. Our love of story enfleshed this in movies, where the past, present and future was interpreted in a multimedia format.

We came to know our world more deeply, a world of billions and billions of people on a fragile planet in space, and wondered about the future of the individual and of the many.

Part 2 - Art And Democracy As Concept

In his book “The Art Spirit” (first published in 1923), Robert Henri wrote:

“Art when really understood is the province of every human being. It is simply a question of doing things, anything well. When the artist is alive, in any person, whatever his kind of work may be, he becomes inventive, searching, daring, self-expressing, creative. He becomes interesting to other people. He disturbs, upsets, enlightens, and he opens ways for a better understanding.” (4)

This democratic view of art-making, this inclusive attitude, marked the 20th century. The Personal Voice emerged strongly and distinctly from the Institutional. It challenged the accepted subject matter, media, and display that had marked the art world of the previous centuries and re-asked the question: “What is Beautiful?”.

After the freshness of the Impressionists, and the horrors of World War 1, Dada came on the scene celebrating the everyday iconoclastically. Think of Marcel Duchamp and his Readymades, eg “Fountain”, which was a urinal signed R Mutt from 1917. It paved the way for a dialogue between Art and the issues of contemporary life for the common person, not just the elite. It also worked in synergy with the development of photography, where the whole world was potential subject matter, and the images made, easily disseminated.

There evolved a use of Installation, Collaboration, Mixed Media and Multimedia, together with Ephemeral and Relational Aesthetics and Process Art. There was spill over to include elements of dance and music. Paralleling this was a blurring of the line between Craft and Fine Art. And in the beginning of the 21st century, there was a commercial resurgence in the popularity of the Handmade, where the mark of the maker and the quirks of each individual article came to be prized by the general public. There was a personal voice in these products that the anonymous mass produced item lacked.

East and West perspectives increasingly cross-pollinated, and mass communications allowed an expanding access to concepts of Meditation, Mindfulness, Intention and Ritual. Taken out of the specifically religious context, there could be a rediscovered sense of sacredness, of connection to a larger being, experienced in the natural world as well as in the daily and repetitive. Words like Pedestrian, Quotidian, Common, Manual, Daily, Domestic, and Routine could inform subject and practice, and ask the questions: “What is Sacred? What is Profane?”. Visual iconography included the everyday: hands, faces, bodies, flags, crockery, pages, steps, newspapers, timetables, texts and “Selfies”. And Metonymy merged the Personal and the Iconic.

The openness of this vision served as a format to reinterpret old themes. Installation allowed an exploration of interaction which spilled over into the space of the viewer in a way that a single canvas or sculpture had not been able to do. Gwyn Hanssen Pigott grouped ceramic vessels echoing Landscapes, Still Lifes and Portraits, using shape, colour and relationship eloquently. And did it with vessels of the everyday.

Another landmark was Andy Warhol and his Campbell Soup cans:

‘Warhol said of Campbell’s Soup, “I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again.”’ (5)

Others like Judy Chicago, with her Tampon related photolithograph of 1971 “Red Flag”, and “Dinner Party” Installation of 1979, tapped into their strong personal commitment to Feminism and how the most basic and previously taboo details of life for a woman were now valid subject matter. The Domestic which had been trivialised for so long, could now be elevated to the status of, and understood as Ritual.

With this embrace and exercise of a Personal Voice there was an implicit affirmation: “I am one person. This is the truth of how I see my world. And I am unique.” And there was a glory and freedom in this. Artists such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye could explore what had always been sacred to her as an Australian indigenous person, and reinterpret it in paint for an uneducated, and previously unappreciative audience. Gordon Bennett teased out his own themes relating to his mixed Aboriginal/White heritage. Ron Mueck and Patricia Piccinini delved into what it means to be human. And Vipoo Srivilasa could articulate the intricacies of dual nationality and sexual identity through the medium of ceramics.

The elevation of the humblest details of life combined with the compulsion many artists felt to "Bear Witness”. It informed their work examining themes of lived injustice: political protest, freedom struggles, equal rights, and discrimination, challenging the accepted histories and social paradigms. Artists such as Betye Saar in the United States developed characters such as Aunt Jemima, a domestic servant, asking the viewer to look again at the truth of the experience of black Americans. She also reflected a burgeoning dissatisfaction with the pace of civil rights reform.

In Australia, artists like Fiona Foley, Karla Dickens and Michael Cook expressed similar issues in their work. Dadang Christanto produced work relating to his experience growing up in Indonesia under political oppression and genocide eg. “They Give Evidence” (1996-7) which was an installation of rows of clay figures holding clothes symbolising persons who had disappeared after being taken from their homes by government forces.

The concept of bearing witness was also used by institutions to give a human voice to national situations eg. the Australian War Memorial’s Offical War Artist program where an artist has been embedded with military forces during conflicts and peacekeeping missions. War artists such as Ben Quilty showed the human face of combat in an increasingly intimate way, thereby validating the individual personal experience of the soldiers with whom he worked.

And so, Art provided a means of communicating the content and character of contemporary events and perspectives in a way distinct from mainstream media. It could touch people in ways that echoed their own lives. It could enlighten social conscience.

Part 3 - Democracy As Interpreted For This Exhibition

My own art practice revolves around ceramics and multiples, the use of a unit repeated. The flexibility of this approach allows me to explore many themes but this time I wished to look at the importance of the Individual to the Whole and how this related to the “One Vote, One Value” core of Democracy.

The role of the individual is central to my practice. Only one thing can be done at a time, one piece touched, brushed, sponged, and even a large work is completed one day, one section, one firing at a time. Aligned with my ability, my treatment of any one unit is based on what that unit needs to be composed and completed, balanced with the part it will play in the larger whole. I work on wholes which aggregate to larger wholes. It means that I have to treat each piece and each day as unique while keeping one eye on the bigger picture. And what is my best for any particular piece or day has to be accepted and worked with honestly and openly. The similarities and differences of each day are inherently part of the work. My acceptance of them is an acceptance of myself, and allowing myself to collaborate with materials rather than dominate them makes the path much easier.

The other factor which energises my practice is being part of a group of like-minded artists who work in many different media. In this group each person and their art are respected. It doesn’t mean we don’t have standards, but that those standards are used to spur each of us to make better, more visually expressive work, rather than foster competition. That inclusive, respectful attitude to each other is then reflected back to each individual, opening each artist’s mind to creatively engage with concept and material, and with their own life.

So from this actively democratic platform, I delineated some critical ideas:

The Individual is intrinsic to and contributes to the Whole, and the Whole changes in a meaningful way with the loss of any single individual.

Individuals share both Commonality and Uniqueness.

Despite being One of Many, the Individual Voice is still heard.

There are a variety of relationships between the Majority and the Minority, and this can touch on our sense of self and the “other” ie. that which is not me.

There are a variety of Institutions which arise to serve the needs defined by the populace.

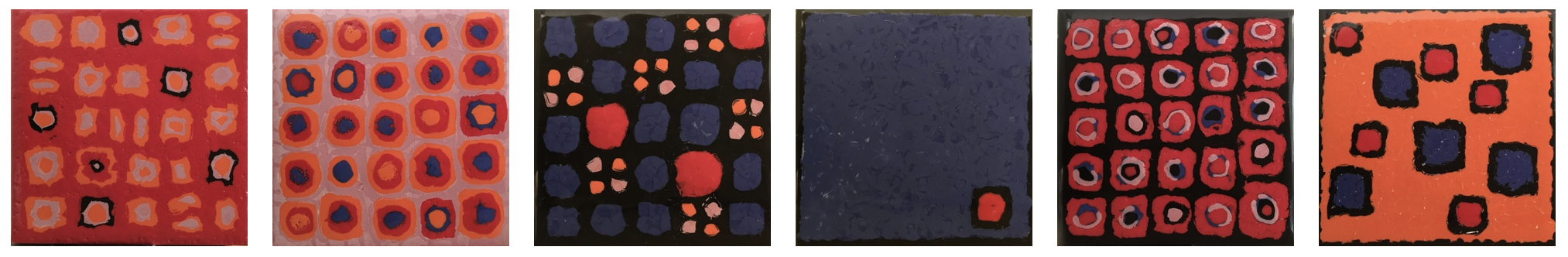

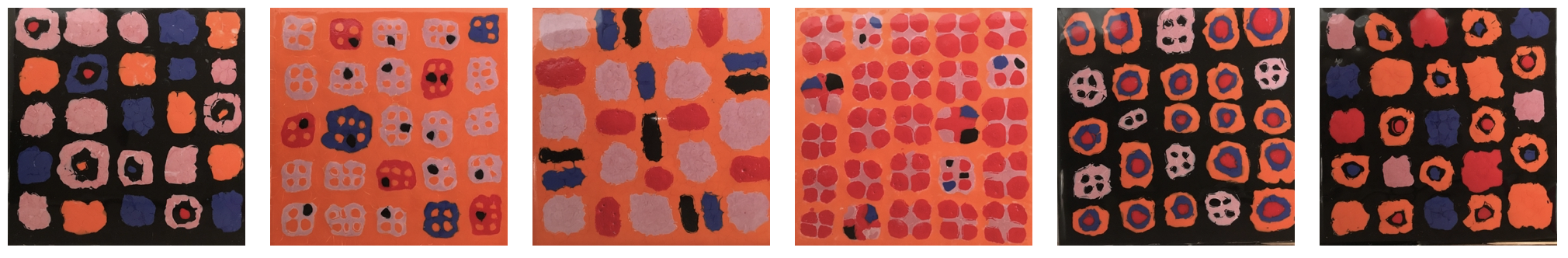

I began this interpretation with identical 20 x 20 cm commercially available tiles and finished them with a “DNA” of 5 glazes. These were then backed so that they could be mounted in a grid-like manner on a wall. Each tile is similar in so many ways to the others but each one’s unique character is obvious. Installed on a large wall their relationships can be seen, and the importance of each one’s presence and position affirmed. They form my Electoral Roll. The variety of colour groupings can speak of the fluidity of Majority/Minority groupings, and in order to achieve a visual balance, I have to understand both the dynamics within each tile and between neighbours.

I was also interested in the concepts of Recognition and Difference. In my mind, Recognition is intricately linked with Respect but includes an element of witnessing to that Respect. Seeing and grasping, truly perceiving and then knowing more deeply, offer satisfaction and affirmation to both the seer and the seen. When an action is taken based on this new knowing, Recognition takes place. In the context of a Democracy, that witnessing is done legally and culturally. Simple icons of an eye and a hand - the seeing and grasping - are the tools I use to illustrate this.

Difference is a rich notion too. At the most basic level, it can be seen in the idea of the “Other” - “that which is not me”. But that simple dichotomy doesn’t illustrate the nuances of similarity and contrast, interdependence and tension which inform any human relationship or any artwork. Uniqueness is the one thing we all have in common, but apart from that our shared, and unshared specifics look like an infinite set of Venn diagrams. I hope that my multiples can be an iteration of that beauty of difference and similarity, teasing out a few contrasts at a time.

I then change the focus to the forms taken by groups. Once many individuals get together to achieve a goal, how does that look? The multiple institutional models found in a democratic state are fleshed out using embroidered canvas and porcelain flowers. Tapestry and fabric are often used as metaphors for lives or society, and I juxtapose tiered porcelain to suggest hierarchies, networks and single units. Like salt shakers and cutlery maps on a table top, a visual vignette can sometimes illuminate elements of relationships more clearly than words.

The dinner table is also an apt setting for exploring Domestic Policy and Human Rights. Utilitarian dishes become canvases to examine associations, collaborations and interdependence, and these themes can be dealt with using sgraffito and very basic, androgynous pictograms.

The many goals generated and the ensuing problems which occur when a group of individuals tries to work out how they wish to be, resonate with the visual metaphor of Mountains. This allows me to ask the questions: “How do you climb a mountain?”, “How do you move a mountain?”. The answers I come up with are: “One step at a time”, One stone at a time”, and this again speaks of a small thing repeated, bringing about a large positive achievement.

The process of this change, an example of which is the Same Sex Marriage Referendum, is one which calls on each elector. It involves them pondering the issue to a greater or lesser extent, being exposed to new ideas, and hearing the opinions of others. And lastly, it necessitates them exercising their right to vote. It’s not always a comfortable process, and so this Responsibility takes the shape of shoulders, individual sculptures, of a part of our anatomy involved with bearing a load and laden with physical memory. Despite the discomfort of this responsibility, the process allows for a ongoing human cultural evolution.

The use of ceramics embeds this content for me in a way which echoes the importance of the small, unassuming unit to the whole. After all, I am simply using dirt (as in clay and glaze), bathroom tiles and canvas. The exhibition and any attendant beauty that might then be generated require me to work collaboratively with those ideas and materials. It doesn’t matter that they have a voice. That’s the whole idea.

And so I return to my original questions:

Does it (Democracy) work?

Does it matter what the individual thinks?

Does an individual have any power to shape their own life let alone the country in which they live?

I would have to answer: Yes.

The corollary to this is that You and I, we both Matter.

And that our power lies in the knowledge that we can achieve anything by taking things just one at a time.

Sources

Lincoln, A, The Gettysburg Address, 2018, Abraham Lincoln Online, viewed 26 April 2018, http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm

Bovard, J 1994, Lost Rights: The Destruction of American Liberty, St Martin’s Press, New York USA.

Laurence, R, Andy Warhol’s 10 most memorable quotes, 4 August 2016, BBC, viewed 26 April 2018, http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20160804-andy-warhols-10-most-memorable-quotes

Henri, R 1923, The Art Spirit, 2007 edn, Basic Books, New York USA.

MoMALearning, Campbell’s Soup Cans, MOMA New York, viewed 26 April 2018, https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/andy-warhol-campbells-soup-cans-1962

The opinions described in this essay are those of a white Australian, and I wish to acknowledge that this limits the scope of the background described.